argan.ai: From buzz to basics – AI for investors

This article was originally written in Dutch. This is an English translation.

During conversations with investors, I increasingly hear the term ‘AI washing’. But what is AI today, and what is its role in tomorrow’s investment team?

By Reza Kahali, Fund Manager and Chief Executive Officer, argan.ai

As a student, I built Bayesian networks to estimate stock volatility. At GSK, we developed “digital twin” models to simulate machines for the production of asthma medication. At NN IP (now GSAM), we worked with completely different models to generate investment ideas. At the time, all of this was already classified as AI.

But since GPT-3, we mainly associate AI with generative language models that produce data. This is really different from, for example, the model used by the Tax and Customs Administration to detect fraud. That is a discriminative model that does not generate data but classifies it.

And AI analysts or agents? These are the same language models that you use to mimic an autonomous agent. Think of Agent Smith from The Matrix. You mimic by initiating a recursive process through question-and-answer interactions. Interactions between the language model and, for example, the internet, other language models or planning algorithms.

I want to talk about the use of this technology, not to make processes or administration more efficient, but within the investment process – where the opportunities and obstacles are greatest. I will discuss my most prominent challenges. I will leave out topics such as cognitive investment biases of AI within the investment process.

To understand these challenges, we must start at the beginning: machine translation and speech synthesis. In 2016, I conducted econometric research for macro simulations. Machine translation was developing rapidly and was a huge source of inspiration. Whether you are talking about consumer price series or word series, both are time series.

A few years earlier (2014), Sutskever (one of the founders of OpenAI) and others described a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network that encodes a sentence into a fixed vector, after which a second LSTM decodes a new sentence. However, the researchers noticed that a single fixed vector containing all the text and recursion was a bottleneck. They introduced the concept of “soft attention” to solve this. With attention, the model can activate relevant parts of the text during decoding. This made the computing power more efficient.

In 2016, a senior researcher at Ortec Finance pointed me to the paper “WaveNet”. “You really need to look at this for time series,” he said. I was amazed. WaveNet (2016) showed that convolutional networks can also model and generate time series without recursion. In their case, the series was raw audio.

And to top it all off, in 2017 Vaswani and others introduced the Transformer model with self-attention. There was no more recursion or convolutions, making it more parallelisable and enabling very large models. Since then, Transformers have been at the heart of almost all modern AI systems.

The big challenge is that these foundations are based on a static world. Language does change, but very slowly (read some 19th-century literature, for example). Markets and the economy are more dynamic.

The first stumbling block is a familiar one: overfitting. A model that learns too well on historical data and performs worse on new data. Fine-tuning large models yielded fantastic results in the tests. But with new data, the AI analysts did not generalise well. Literature and experience teach us that a mix of smaller, task-oriented models with careful context management is more stable and predictable. Much better than one monstrous model.

The second problem is inherent in generative models: hallucinations. Language models invent “facts” that sound logical but are untrue. Think of a large language model as a compressor of the world: billions of parameters compress and encode patterns. When used, this knowledge is decompressed again. However, the model does not always have enough “bits”. It then fills the gap with the most likely pattern – which sometimes turns out to be incorrect.

Example: compress a photo of a girl with a mole. During compression, the detail of the mole disappears. When you reconstruct the photo, the model fills in that spot with her skin colour. The result is a subtle “hallucination”, a girl without a mole. This is because the model is not optimised to tell the truth, but to sketch the most likely scenario.

In my experience, it helps enormously to provide your AI analyst with authoritative data as a safety net. For example, facts from official databases and official statistics. But techniques such as “Chain-of-Verification” or “DoLa” can also help. However, trusted statistical methods remain useful. Think of stability tests with repeated runs and Monte Carlo simulations.

The third problem is data contamination. Consider, for example, a specialist macro AI analyst who has to give advice during the COVID-19 stock market crash. These models have often already seen studies from 2021–2022 in their pre-training. In the simulation, the analyst makes perfect predictions. Not based on “analysis”, but on “leaked” knowledge.

Adding noise or fictitious variations helps, so that the original pattern is no longer literally present in the data. Domain transfer is also useful: asking similar questions in a new context. The model cannot then simply retrieve the standard answer. In practice, it is not easy to make a neural network forget specific knowledge ex ante.

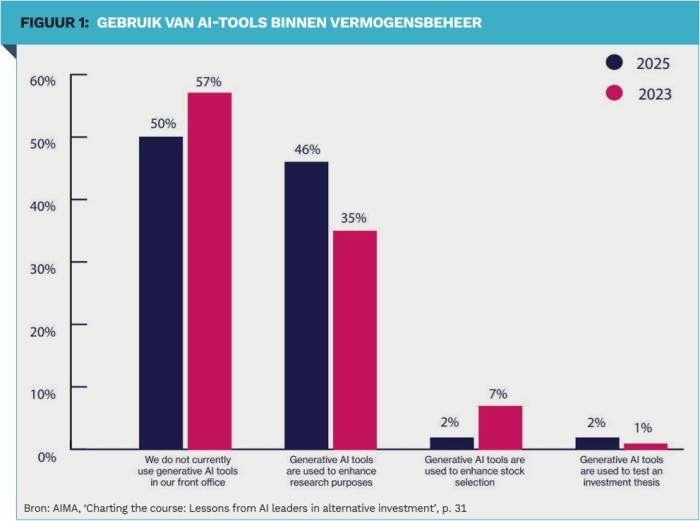

Of course, there are other issues at play within a professional investment team. Consider algorithm aversion. This struck me as a young “quant”. People often rely more on their own judgement than on that of an algorithm, even if the algorithm is better. They prefer to take their own risks and honour their own judgement rather than opt for a consistently predictable result. This is one of the reasons why adoption is low (see Figure 1). However, the opportunities are great.

Suppose, for example, that you want to determine financing stress in the US repo market. Your quantitative model can analyse the difference between the overnight repo rate and the midpoint of the federal funds target range, i.e. the repo spread. The statistical model then assesses whether this difference is abnormal. In addition, your AI analyst reads academic research and the central bank's policy plan. This allows him to estimate whether the policy is expected to generate more or less liquidity. The AI analyst can thus fill in the blind spots in your quantitative models, something that an experienced investment strategist would normally do. For example, your statistical model turns bright red, but your AI analyst indicates that the policy has corrected this.

I am therefore convinced that the future of investing lies in collaboration between humans and AI. AI analysts and models process data at lightning speed and execute strategies. Surrounding them are human professionals who are responsible for creative thinking, setting out strategies and coming up with out-of-the-box ideas.

These models cannot yet be successfully tasked with, for example, developing a completely new investment philosophy or coming up with radically different perspectives. We humans are (for the time being) better at that.

|

SUMMARY The fundamentals of AI are based on a static world. That works well with language, which changes only slowly, but markets and economies are dynamic. Modern AI offers enormous opportunities, but struggles with the familiar headaches: 1. Overfitting 2. Hallucinations and 3. Data contamination. Solutions include small specialised AI agents, clean and authoritative data sources, verification chains, stochastic runs or domain transfer. The future lies in collaboration between humans (creativity) and a combination of AI and classical models. |